-

First meeting held in a small chapel in the slums of New York City on East 14th Street.

June 24, 1973

- Church Moves to New Jersey. There Are about 30 Members. 1976

- Postage Stamp Gardens 1978

-

Everyone Moves (about 100 People) to Colorado

1979-1980

- Church Starts in Texas 1980

-

Begin Horse Farming

1981

- First Fair August 8, 1988

- Opened Visitor Center 1994

- First Sustainability Classes Given to Public 19??

- Craft Barn Opened 1997

- First Fair with Over 10,000 Visitors 2001

- First Fair with Over 20,000 Visitors 2014

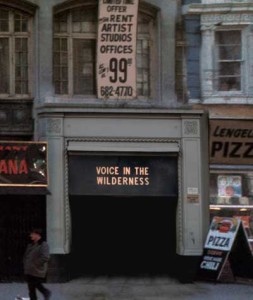

Homestead’s beginnings go back to June of 1973, when Homestead’s founders Blair and Regina Adams moved into the Hells’ Kitchen area of Lower East Side Manhattan in New York. There, they rented an undersized cold-water flat in which to live and started a small peace church in a chapel which had formerly been a discotheque bar and a crash pad for substance abusers and other down-and-out street people.

Homestead’s beginnings go back to June of 1973, when Homestead’s founders Blair and Regina Adams moved into the Hells’ Kitchen area of Lower East Side Manhattan in New York. There, they rented an undersized cold-water flat in which to live and started a small peace church in a chapel which had formerly been a discotheque bar and a crash pad for substance abusers and other down-and-out street people.

People of many backgrounds—South American, Puerto Rican, African American, Jewish, Italian, German, Polish, Russian—began attending meetings. Soon a small cluster of believers found themselves easing out of what they increasingly saw as the competitive frenzy of urban squalor and squander that surrounded them in New York City. Instead, they began to dedicate themselves to cooperating with and helping each other. Before long, they realized that, although they all still lived in their separate slum tenements, they nonetheless had almost inadvertently become a community—if of nothing else, then of heart and mind, of values and ideals, of hopes and dreams.

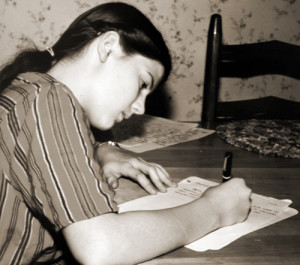

Home Education

They immediately saw the need to impart to their children the cooperative values they themselves were learning. They knew that this would not be possible without shifting to a different kind of education. The educational model that had produced the pervasively competitive and specialized culture around them seemed destined to produce only more of the same. So they extensively studied education from every angle they could find, always seeking something that emphasized the wholeness of life. Their search reinforced a growing conviction that education would have to somehow be deindustrialized. Otherwise, they didn’t see how they could ever achieve the results and the life they sought, or sustain such results if they were achieved. So, first, they set about to educate their children themselves and in their own homes.

They immediately saw the need to impart to their children the cooperative values they themselves were learning. They knew that this would not be possible without shifting to a different kind of education. The educational model that had produced the pervasively competitive and specialized culture around them seemed destined to produce only more of the same. So they extensively studied education from every angle they could find, always seeking something that emphasized the wholeness of life. Their search reinforced a growing conviction that education would have to somehow be deindustrialized. Otherwise, they didn’t see how they could ever achieve the results and the life they sought, or sustain such results if they were achieved. So, first, they set about to educate their children themselves and in their own homes.

Growing Their Own Food

Next they began to seek out patches of ground in the New York metropolitan area where they could grow at least a little of their own food. In the 1970’s, as these efforts focused their attention across the Hudson River, in New Jersey, they began to see more and more how the way they had lived had actually cut them off from fully and directly participating in all those activities that were essential to human life. This included matters as simple but as absolutely necessary as eating; but it also included other activities of the heart and mind, like teaching their own children. And, in that sense, they found that their old lifestyle had, ironically, cut them off from living. So they now eagerly thrust their hands into the soil, and even talked about how rich and good simple dirt smelled. Members continued to teach their own children and came to know the rewards of watching them learn and learning with them.

Next they began to seek out patches of ground in the New York metropolitan area where they could grow at least a little of their own food. In the 1970’s, as these efforts focused their attention across the Hudson River, in New Jersey, they began to see more and more how the way they had lived had actually cut them off from fully and directly participating in all those activities that were essential to human life. This included matters as simple but as absolutely necessary as eating; but it also included other activities of the heart and mind, like teaching their own children. And, in that sense, they found that their old lifestyle had, ironically, cut them off from living. So they now eagerly thrust their hands into the soil, and even talked about how rich and good simple dirt smelled. Members continued to teach their own children and came to know the rewards of watching them learn and learning with them.

Home Birth

They also began to give birth to their babies at home. They saw that birth was not a pathology that belonged in a hospital but the beginning of life that should begin in the place that best nurtured life—the self-sustaining home. More and more, they just wanted to live, really live. And when their elderly died of having fully lived, their children and grandchildren didn’t want to give death the final victory by running from it—they wanted to overcome it with what had always held their lives together and given them meaning and purpose: self-sacrificing love. So they took care of their elderly and disabled, too, cherishing the opportunity to learn from the accumulated wisdom of a long life and to serve those who now fought to continue overcoming with love the most trying of life’s circumstances, the greatest of its battles.

They also began to give birth to their babies at home. They saw that birth was not a pathology that belonged in a hospital but the beginning of life that should begin in the place that best nurtured life—the self-sustaining home. More and more, they just wanted to live, really live. And when their elderly died of having fully lived, their children and grandchildren didn’t want to give death the final victory by running from it—they wanted to overcome it with what had always held their lives together and given them meaning and purpose: self-sacrificing love. So they took care of their elderly and disabled, too, cherishing the opportunity to learn from the accumulated wisdom of a long life and to serve those who now fought to continue overcoming with love the most trying of life’s circumstances, the greatest of its battles.

Journey to Colorado

Each new level of participating brought unforeseen changes in their thinking, their feelings, their attitudes about life. So their relationships with each other, with creation and with God began to change, too. It came to them slowly that they were on a journey, not just back to their Anabaptist roots, but back to life, a journey back down to earth with their bodies and back up to heaven with their souls. As all the pieces fell into place and the whole began to emerge, they felt life expanding in every direction—in breadth, depth, height and width—until a fully formed body of people, a community that could carry all that was essential to life, was finally being formed. They often described all that was changing in their lives as their “journey home.”

Each new level of participating brought unforeseen changes in their thinking, their feelings, their attitudes about life. So their relationships with each other, with creation and with God began to change, too. It came to them slowly that they were on a journey, not just back to their Anabaptist roots, but back to life, a journey back down to earth with their bodies and back up to heaven with their souls. As all the pieces fell into place and the whole began to emerge, they felt life expanding in every direction—in breadth, depth, height and width—until a fully formed body of people, a community that could carry all that was essential to life, was finally being formed. They often described all that was changing in their lives as their “journey home.”

But such journeys had always first demanded an exodus from one land before a people could find another. Soon, gardens weren’t enough—they wanted to expand this realm of wholeness they had discovered, this realm of their new-found freedom to live. So they began looking for a larger piece of land and ended up in Colorado. About a hundred, close-knit people by now, they began the move from New Jersey. It took them six months to move everyone, since it took time to secure sufficient housing and to set up new businesses. In every way, moving west was a new experience for these easterners, many of whose roots went back for generations in the New York metropolitan area. One brother had never seen a tumbleweed, so he stopped, picked up the first one he saw, boxed it and sent it home to his mother.

But such journeys had always first demanded an exodus from one land before a people could find another. Soon, gardens weren’t enough—they wanted to expand this realm of wholeness they had discovered, this realm of their new-found freedom to live. So they began looking for a larger piece of land and ended up in Colorado. About a hundred, close-knit people by now, they began the move from New Jersey. It took them six months to move everyone, since it took time to secure sufficient housing and to set up new businesses. In every way, moving west was a new experience for these easterners, many of whose roots went back for generations in the New York metropolitan area. One brother had never seen a tumbleweed, so he stopped, picked up the first one he saw, boxed it and sent it home to his mother.

The community couldn’t buy land at first, so they rented a ten-acre farm and bought their first chickens, ducks, geese, sheep and draft horses. They decided to try to begin learning the rudiments of farming on a small scale until they could buy their own land.

As their newly started service and building businesses prospered, in a few years they were able to purchase a 700-acre farm with a year-round stream running through it. It was over eight miles from the closest town, which was small, not much more than a village. So they felt more isolated from other people than they had wanted to be, but in a way, this probably ended up being for the best, since it gave them the opportunity to learn to farm without having to take too much time out for a constant stream of visitors (though already many people from all over the world were visiting their farm). And, as it turned out, they needed a lot more time to learn how to farm than they had originally anticipated. And then it took even more time to learn how to farm with horses, about which lots of stories can be told. Before too long, they succeeded in the horse farming and were planting gardens, vineyards, potatoes, oats, flax and alfalfa. After they had mastered the basics, they were ready to move on and try to share their life, and what they had learned, with others.

As their newly started service and building businesses prospered, in a few years they were able to purchase a 700-acre farm with a year-round stream running through it. It was over eight miles from the closest town, which was small, not much more than a village. So they felt more isolated from other people than they had wanted to be, but in a way, this probably ended up being for the best, since it gave them the opportunity to learn to farm without having to take too much time out for a constant stream of visitors (though already many people from all over the world were visiting their farm). And, as it turned out, they needed a lot more time to learn how to farm than they had originally anticipated. And then it took even more time to learn how to farm with horses, about which lots of stories can be told. Before too long, they succeeded in the horse farming and were planting gardens, vineyards, potatoes, oats, flax and alfalfa. After they had mastered the basics, they were ready to move on and try to share their life, and what they had learned, with others.

The Journey to Texas

So now they looked for a place closer to more people. Another fellowship had started in Texas, and then a Baptist church offered to give them a church building, the first they’d ever owned. They moved to central Texas, bought land near Elm Mott (centrally located between Austin and Dallas), sold their farm in Colorado and started anew on a piece of land known as Brazos de Dios (the original name that early Spanish explorers to Texas had used for the Brazos River, which borders the property). Here, they worked together to set up housing, plant gardens and vineyards, repair and build fences, build buildings and workshops.

So now they looked for a place closer to more people. Another fellowship had started in Texas, and then a Baptist church offered to give them a church building, the first they’d ever owned. They moved to central Texas, bought land near Elm Mott (centrally located between Austin and Dallas), sold their farm in Colorado and started anew on a piece of land known as Brazos de Dios (the original name that early Spanish explorers to Texas had used for the Brazos River, which borders the property). Here, they worked together to set up housing, plant gardens and vineyards, repair and build fences, build buildings and workshops.

There were some rough spots at first—a few people unfamiliar with the community confused them with David Koresh’s notorious group in Waco, a group that hit the headlines at the same time that Homestead was just settling in. But before the tragic finale of this group had occurred, the Homestead community had already celebrated their first Fair in Texas, and the local television station had done an especially favorable program on it. Now, during the ensuing crisis, television stations swept in from Dallas, Houston and all over central Texas to help make clear that this “isn’t the same group,” that the two were “as different as night and day.” The locals and many newspapers rallied once again to their support, and things soon settled down. All the while, they kept working until finally everything previously described had become a reality.

Whenever they stopped to take a breather and look around, they marveled at what had come to pass, at how far they had come from their old New York days on East 14th Street, in the slums of Hell’s Kitchen. It all seemed like a dream, and people who had known them longest would even tell one of their oldest members, “I don’t know anyone whose dreams have come true like yours.” And they knew it was so.